How an LDS Family Helped Restore the Joseph Smith Homestead, Heal a Town, and Safeguard Sacred Ground

Introduction

Sacred history does not only live in scriptures. It clings to soil, to timber, and to walls that once rang with laughter and weeping. For members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter day Saints, the small village of Palmyra in upstate New York carries the spiritual weight of beginnings. It was here that a young boy named Joseph Smith sought God, opened his heart in prayer, and received a vision of the Father and the Son. It was here that a family of modest means struggled through debt, harvest, and hardship while unknowingly standing on ground destined to be holy. And it was here that hostility eventually scattered the Saints and left behind only memory.

By the dawn of the twentieth century those memories risked fading. Locals saw the old Smith farm as just another piece of farmland, and the grove of trees where Joseph had prayed was in danger of being logged or forgotten. To the faithful Saints living across the United States and beyond, this was unthinkable. The Restoration was no abstract philosophy, it was anchored in time and place. If the Church was to preserve the testimony of its origins, it needed more than printed pages. It needed to safeguard the very land where heaven touched earth.

“Remember the worth of souls is great in the sight of God.”

— Doctrine and Covenants 18:10

Preserving the land was about more than acreage. It was about the souls who would someday walk it. Church leaders understood that a farm, a grove, and a hill could testify just as powerfully as sermons if they were treated as sacred witnesses. Preserving holy ground required not only deeds and dollars, it required living stewards. In 1907 Apostle George Albert Smith secured the purchase of the Joseph Smith farm, ensuring that the soil itself would be in Church hands. Yet the land alone was not enough. Someone had to live there. Someone had to tend the orchards, welcome visitors, and above all mend decades of hostility between the Church and the people of Palmyra.

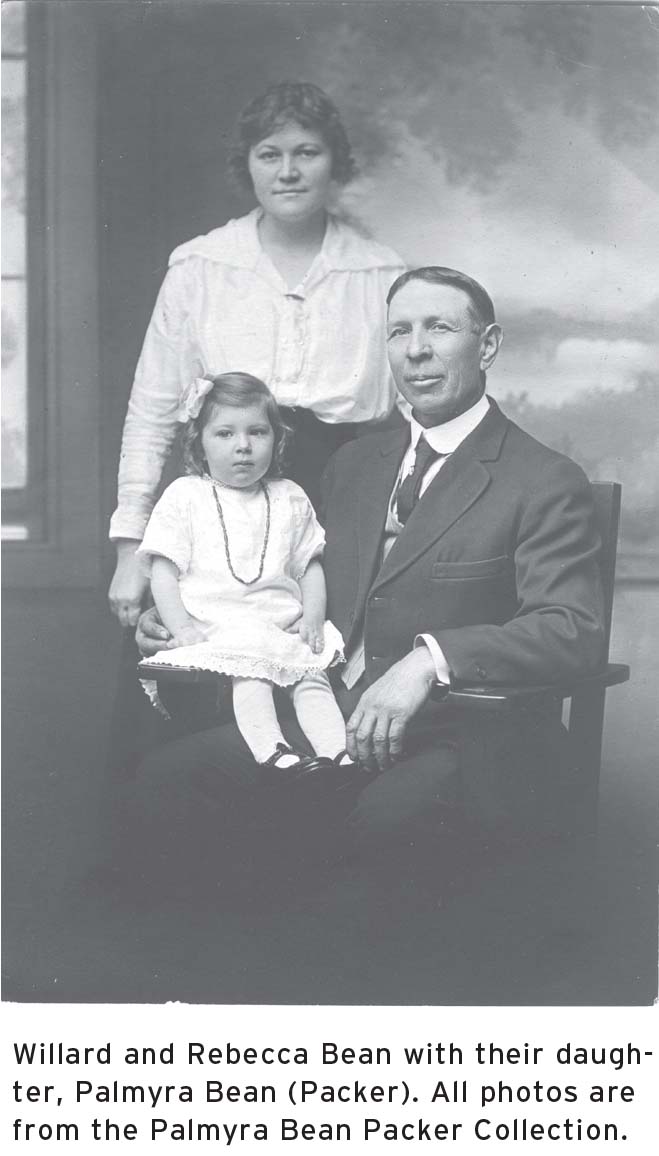

That responsibility fell upon Willard Washington Bean and his wife Rebecca Rosetta Peterson Bean. Newlyweds with the freshness of youth and the fire of testimony, they were called in 1915 by President Joseph F. Smith to uproot their lives in Utah and make a home in Palmyra. Their assignment sounded straightforward, maintain the Smith farm, open the doors of the homestead, and represent the Church in the region. Yet hidden within that call was an undertaking so great that few would have dared to accept it. The Beans were not only caretakers of property, they were emissaries of healing.

When the Beans first arrived, they stepped into a community that remembered Mormonism not with fondness but with suspicion. The shadow of the past loomed large. Local citizens still told stories of Joseph Smith and the “gold Bible,” but these stories were often colored with derision and ridicule. Merchants eyed the newcomers with distrust, and many families refused to welcome them into their circles. The Smith farm itself, though deeded to the Church, remained a place of curiosity and even mockery to many in the region. What could a single family do to change that?

The answer would unfold over nearly a quarter of a century. For twenty four years, the Beans tilled, testified, and endured. They raised children under the same roof where Joseph had once lived. They turned a house of exile into a home of belonging. They planted gardens that fed not only their table but the hearts of skeptical neighbors. They told and retold the story of a boy prophet to thousands of visitors who came searching for the roots of their faith. Slowly, almost imperceptibly, a hard town softened.

The story of the Beans is not a tale of grand sermons or fiery debates. It is a story of small acts done faithfully. It is the tale of a boxer turned missionary who found his greatest fight was not in the ring but in winning the trust of his neighbors. It is the tale of a faithful wife and mother who lived the gospel with such gentleness that barriers crumbled around her. It is the tale of children born and raised in consecrated service, growing up to carry forward the witness of their parents. Above all, it is the tale of how God uses ordinary families to do extraordinary work.

“By small and simple things are great things brought to pass.”

— Alma 37:6

The Beans’ mission to Palmyra stands as a testament that history is not just written by events, but by families who choose to consecrate their lives. Their service reminds us that the Restoration was never meant to be a dusty chapter in a book. It is a living reality, rooted in places that still exist and in people who still remember. As we trace the path of Willard and Rebecca Bean, we see not only how the Joseph Smith farm was restored, but how a community was healed and a Church strengthened.

The Farm, the Grove, and the Smith Family

When Joseph Smith Sr. and Lucy Mack Smith brought their family to western New York in the winter of 1816 and 1817, they were following the same migration pattern that had drawn thousands of New England families into the Finger Lakes region. The soil was rich, the forests dense with timber, and the promise of new beginnings seemed almost within reach. The Smiths were a family of vision and labor, yet they also carried the burdens of financial struggle. In 1818 they acquired a hundred acre parcel just outside the town of Palmyra, and on that land they built a log home of rough timbers. It was small, it was plain, and it was typical of the frontier. But within its walls a young boy would grow to ask questions that would change the world.

Life on the farm was difficult. Each child was expected to contribute to the family’s survival. Clearing trees, hauling stones, planting crops, tending animals, and repairing tools consumed most days. Debt weighed heavily on Joseph Sr., and the land was only partly paid for. Yet the Smiths endured, and their efforts to live uprightly amidst poverty planted seeds of faith that would bear eternal fruit. For members of the Church today, the image of the Smith family laboring in the fields serves as a reminder that God often chooses the humble and the obscure to accomplish His greatest works.

“The Lord seeth not as man seeth, for man looketh on the outward appearance, but the Lord looketh on the heart.”

— 1 Samuel 16:7

On this very farm young Joseph wrestled with questions about truth and salvation. He read the Bible by firelight, he listened to preachers from competing denominations, and he felt the weight of confusion pressing on his soul. Just a short walk from the family cabin stood a grove of trees. In that grove, shielded from the noise of the world, Joseph fell to his knees in prayer. There, in answer to his humble plea, the heavens opened. The Father and the Son appeared and gave their message, and the Restoration of the gospel was set in motion. Every Latter day Saint who visits the Sacred Grove today is retracing the steps of that boy, breathing the same air, and hearing the same rustle of leaves.

The preservation of that grove was no accident. In 1860, long after the Smiths had been driven west, a man named Seth T. Chapman purchased the farm. Though not a member of the Church, he and his family left a portion of the land untouched. While other farmers cleared fields to make way for more crops, the Chapmans spared that woodlot. By providence and restraint, the trees were kept. When Church leaders later reacquired the property, they found not only the homestead but also the grove still standing. To this day, Saints believe it was the hand of the Lord that preserved those trees until they could once again be consecrated.

The Smith farm and the Sacred Grove are not only historic relics but living witnesses. They remind us that God reveals Himself to those who sincerely ask. They remind us that the Restoration began in a small corner of the earth, not in the courts of kings or the halls of scholars, but in the prayer of a farm boy. They also remind us that sacred things must be preserved by the hands of those willing to sacrifice. The land itself was sanctified by prayer, and its survival through decades of neglect is evidence that God remembers His covenants with His people.

“If any of you lack wisdom, let him ask of God, that giveth to all men liberally, and upbraideth not, and it shall be given him.”

— James 1:5

From Purchase to Presence

By the early years of the twentieth century, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter day Saints had grown into a thriving body of Saints in the Mountain West and abroad, yet the earliest sites of its history remained out of reach. Palmyra, the Sacred Grove, and the Smith family farm were places spoken of with reverence in Sunday meetings and in family scripture study, but they belonged to others. President Joseph F. Smith and other leaders felt a deep urgency to preserve these locations before they were altered or lost forever. The Saints were entering an era where memory needed to be anchored by stewardship.

In December of 1905, President Joseph F. Smith stood upon the land of the Smith homestead after attending the dedication of the Joseph Smith Birthplace Memorial in Vermont. He gazed across the fields and into the grove and expressed his heartfelt wish that the Church could secure the property. That longing soon turned into action. In 1907, Apostle George Albert Smith was sent east with authority to purchase the farm. After careful negotiations with the Chapman family, who had owned the land since 1860, he secured the deed for twenty thousand dollars, a significant sum in those days but one gladly offered to safeguard sacred ground.

The transaction was more than real estate. It was the return of a birthright. After nearly a century, the Smith farm was again under the stewardship of the Church. Leaders counseled that the property be preserved with care and that the grove in particular be protected from exploitation. George Albert Smith recorded in his diary the joy he felt at finalizing the purchase, and members across the Church rejoiced that the place where the First Vision had occurred was once again safe in the hands of the Saints.

“For behold, this is my work and my glory, to bring to pass the immortality and eternal life of man.”

— Moses 1:39

Owning the farm was only the first step. A deed on paper did not guarantee the goodwill of a community that had once driven the Saints away. Palmyra still held deep suspicions toward Mormonism, and locals regarded the Church with a mixture of curiosity and distrust. Leaders in Salt Lake City knew that the land itself needed caretakers who could represent the Church, work the farm, and slowly build bridges with wary neighbors. It would require a missionary presence, not for months but for years.

In 1915, the call was extended to a newly married couple in Utah, Willard Washington Bean and his wife Rebecca Rosetta Peterson Bean. They had been married only a few months when President Joseph F. Smith summoned them. Their assignment was unlike any other. They were to pack up their belongings, travel across the country, and make their home in the Joseph Smith farmhouse in Palmyra. Their duties included caring for the property, opening the doors to visitors, sharing the story of the Restoration, and cultivating goodwill among townspeople who were not inclined to welcome them.

The Beans accepted without hesitation. They saw the call not as a burden but as a privilege. For them it was not simply an invitation to live in a historic place, it was a summons to consecrate their lives to the work of the Lord. They understood that they would be strangers in a community that did not trust them, but they also knew that God had preserved the farm for a reason. Their faith was simple, their resolve strong, and their willingness to sacrifice unquestioned.

As they left Utah for New York, they stepped into a mission that was meant to last five years. In reality, it would last twenty four.

A Town That Needed Time

The town carried long memories and old prejudices. To many local residents, the arrival of a Mormon family stirred echoes of nineteenth century tensions, when Joseph Smith and his followers had been driven from community after community. In Palmyra, the name of Mormon was still spoken with suspicion. Shopkeepers refused service. Neighbors kept their distance. Children of the town were warned not to play with the Bean children. Even civic leaders treated the newcomers with cold indifference.

The Beans quickly realized that they had stepped into a field that required patient cultivation. The farm itself was work enough, with fences to mend, animals to tend, and land to manage. Yet the greater task lay in healing hearts that had been hardened by rumor and tradition. The couple could have chosen to retreat into isolation, fulfilling their duties quietly and avoiding contact. Instead, they determined that every chore and every conversation would be an act of missionary service.

Rebecca, with her gift for kindness, began baking pies and delivering them to neighbors who had shunned her. She carried food to the sick and quietly offered her help when families faced hardship. Willard lent his strength to mend broken fences, haul heavy loads, and assist farmers who were short of labor. When doors closed, he knocked again. When words were harsh, he responded with warmth. Slowly, almost invisibly, the hostility began to soften.

“Charity suffereth long, and is kind; charity envieth not; charity vaunteth not itself, is not puffed up.”

— 1 Corinthians 13:4

This was not an easy process. The Beans endured years of gossip and prejudice. At times, their children came home from school in tears, bewildered by the insults hurled at their faith. Yet Rebecca comforted them with scripture and hymns, reminding them that discipleship had always demanded patience. Willard spoke with the steady conviction of a man who had once been a boxer and now understood that his greatest fight was not in the ring but in winning the trust of his neighbors. He often said that persistence in love was stronger than any fist.

The turning point came gradually. Families who once whispered against the Beans began to accept small tokens of friendship. A pie at the door, a hand offered in labor, a kind word spoken at the right moment began to erode old walls. Some locals who had refused to step onto the Smith property began to visit, curious to see how this Mormon family conducted themselves. They discovered not fanatics but ordinary people of faith, raising children and cultivating the land with dignity.

By the end of their years in Palmyra, the Beans were no longer regarded with suspicion but with respect. They were invited into civic organizations, welcomed into schools, and asked to speak at community gatherings. The same town that had once bristled at their presence came to honor them as neighbors and friends. The transformation did not happen in a day or a year. It happened through decades of steady faith, proving that the work of the Lord often requires not dramatic gestures but enduring charity.

“Be not weary in well doing, for ye are laying the foundation of a great work. And out of small things proceedeth that which is great.”

— Doctrine and Covenants 64:33

Guiding Pilgrims, Tending the Grove, Teaching the Story

Even while the Beans worked patiently to earn the trust of their neighbors in Palmyra, they also opened their doors to Latter day Saints who traveled from afar to see the places where the Restoration began. In the early twentieth century such journeys were no small task. Saints from the Mountain West often traveled for days by train, and some arrived on horseback or by carriage from nearby states. They came with reverence, desiring to walk the same paths that Joseph had walked and to kneel in the grove where he had prayed.

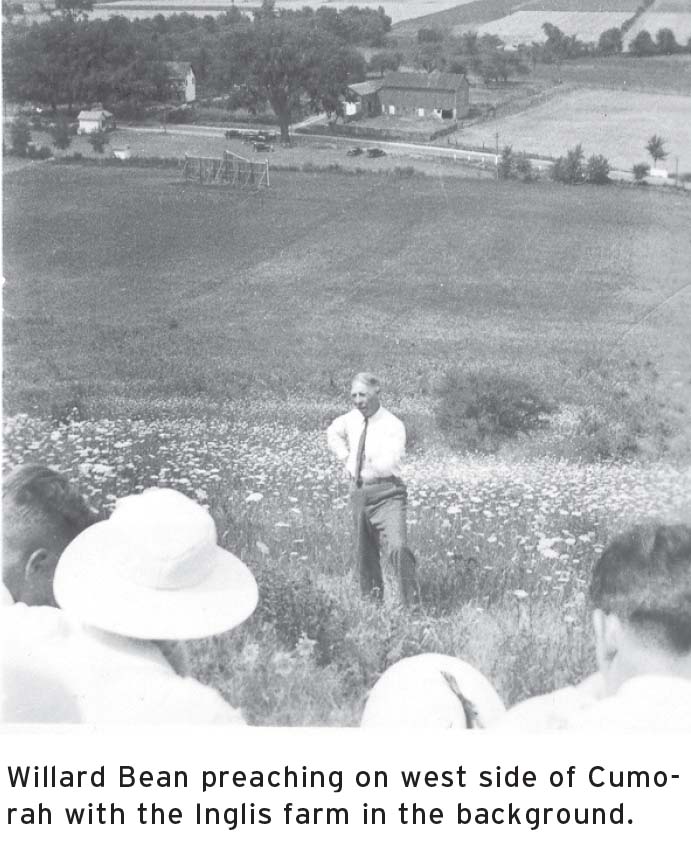

The Beans welcomed them warmly. Visitors were guided through the frame home and shown the fields where the Smiths had labored. Willard would recount the stories of the family’s hardships, their persistence in faith, and the young boy’s search for truth. Rebecca would speak of the home itself, the daily chores, and the family’s determination to endure. Together they painted a picture of a family who lived humbly and yet was chosen to be the vessel of divine work. To many visitors, these tours were more than history lessons. They were spiritual experiences that deepened testimony.

When they led visitors into the Sacred Grove, they did so with reverence. They did not treat it as a curiosity but as a holy place. The Beans encouraged pilgrims to walk quietly among the trees, to find a secluded spot, and to pray as Joseph had prayed. Many Saints recorded in their journals that they felt the Spirit powerfully while in the grove, as if the heavens were still open to those who sought them. The Beans believed that their greatest responsibility was not simply to protect the property but to help each visitor experience the same call to prayer that Joseph had felt.

“Ask, and it shall be given you; seek, and ye shall find; knock, and it shall be opened unto you.”

— Matthew 7:7

Over the years the farm became a living classroom for the gospel. Missionary conferences were sometimes held on the property, with small gatherings in the grove where hymns were sung and testimonies borne. Youth groups from nearby branches would travel to the Smith farm to feel the spirit of sacred history. The Beans themselves often bore testimony in these settings, reminding Saints that the events of the Restoration were not distant legends but living realities connected to real places.

As the number of visitors grew, so did the Beans’ awareness that they were caretakers not only of property but of memory. Every tour, every testimony, every prayer in the grove was part of keeping alive the story of a boy prophet who changed the world by simply kneeling in faith. The Beans understood that their stewardship would ripple far beyond their own lives. They saw it in the tears of pilgrims, in the reverent silence of children walking the grove, and in the renewed faith of missionaries who returned from the farm strengthened for their labors.

To guide pilgrims was to remind the Church that the Restoration was grounded in reality. The Smith family had lived in poverty, had struggled with debt, and had worked the same soil that visitors now touched. The Sacred Grove was not a myth but a preserved wood where anyone could still kneel and ask. In caring for the property and in bearing testimony day after day, the Beans kept the Church connected to its earliest roots.

“Stand ye in holy places, and be not moved.”

— Doctrine and Covenants 87:8

The Hill That Would Not Sell, Then Did

While the Joseph Smith farm and the Sacred Grove came into Church possession in 1907, another site loomed large in both memory and importance. Just a few miles south of Palmyra stood Hill Cumorah, the place where Joseph Smith received the golden plates from the angel Moroni. For Latter day Saints, the hill was more than a landmark. It was sacred ground that carried the weight of scripture and prophecy. To stand on its slopes was to stand at the threshold of the Book of Mormon itself. Yet for many years, the hill remained in the hands of others, and acquiring it proved to be one of the most difficult undertakings of the early twentieth century.

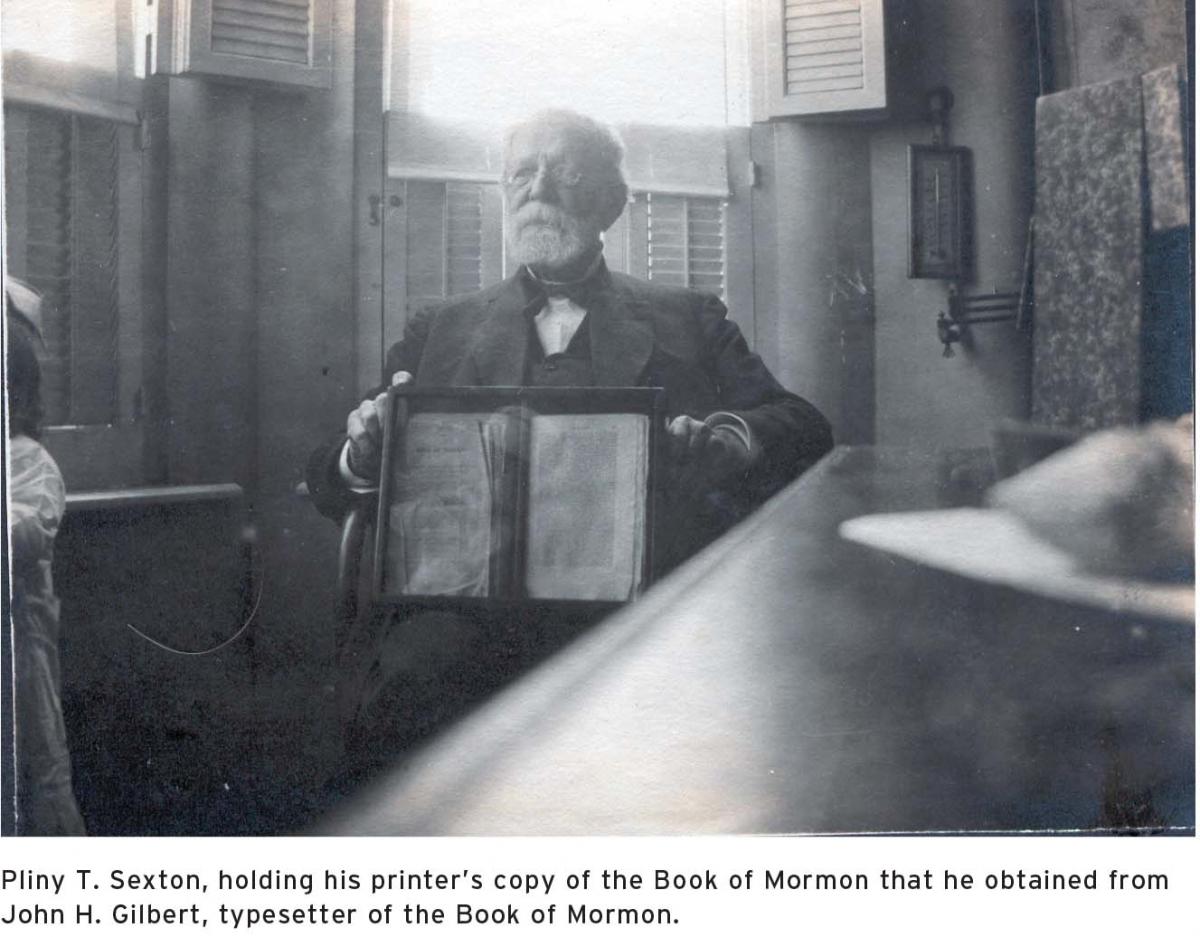

The largest portion of the hill belonged to Pliny T. Sexton, a wealthy and influential local man who was determined not to sell. Sexton had little love for the Latter day Saints, and he understood the symbolic value the hill held for them. He guarded it jealously and often scoffed at offers from Church representatives. At times he hinted at selling for outrageous sums, but even then he seemed to take delight in refusing serious negotiation. His stance hardened as the years passed, and it seemed that Cumorah might remain outside the reach of the Saints forever.

The Beans lived in the shadow of this tension. Willard especially bore the responsibility of keeping the vision alive. He befriended townspeople, softened hearts, and built relationships that would eventually open doors. Though Sexton remained stubborn, others began to see the Beans not as outsiders but as trusted neighbors. When Sexton eventually passed away, the matter of Cumorah passed to his heirs. Negotiations continued, often with setbacks and frustrations, but the foundation laid by the Beans’ decades of goodwill gave the Church leverage it had not enjoyed before.

“For ye have need of patience, that, after ye have done the will of God, ye might receive the promise.”

— Hebrews 10:36

In 1923 the Church managed to purchase a portion of the western slope of the hill. It was a small beginning, but it symbolized progress after years of stalemate. Willard and Rebecca rejoiced quietly, knowing that even a partial acquisition meant that the Lord was moving His work forward. Yet the full hill still remained out of reach. More years of patient effort followed, with continued contact between Church leaders and the Sexton heirs.

Finally, in February of 1928, the long struggle came to an end. The Church successfully purchased nearly the entire hill from the Sexton estate, securing Cumorah for generations to come. When word spread among the Saints, there was rejoicing from Utah to New York. President Heber J. Grant soon announced the acquisition in general conference, testifying that the Lord had opened the way in His own time. A few years later a monument would be erected on the northern crest of the hill, commemorating the angel Moroni and the sacred events that had unfolded there.

For the Beans, the acquisition of Cumorah was both a personal and spiritual victory. They had labored for more than a decade in the shadow of that hill, often hearing townspeople mock the Saints’ desire for it. Through kindness, persistence, and steady missionary work, they had shifted the climate of opinion in Palmyra. What once seemed impossible slowly became reality. The hill that would not sell had finally been placed into the care of the Church.

“The Lord is not slack concerning his promise, as some men count slackness; but is longsuffering to us ward, not willing that any should perish, but that all should come to repentance.”

— 2 Peter 3:9

The story of Hill Cumorah reminds us that sacred places are not gained by force or impatience. They are secured by faith, by endurance, and by the unseen hand of the Lord moving through time. The Beans were witnesses to this process. They saw how years of rejection gave way to triumph, and they understood that their role was not to conquer but to serve. Their lives prove that patience and persistence are as essential in building Zion as vision and zeal.

More Than One Landmark

The Beans’ stewardship was never confined to the Smith farm alone. Their calling was broad, their responsibilities fluid, and their influence far reaching. While the Joseph Smith homestead and the Sacred Grove were the center of their daily life, the family also played a vital role in helping the Church recover other historic properties tied to the earliest days of the Restoration. Theirs was a mission not only of caretaking but of preparation, smoothing paths that would allow the Saints to reclaim and preserve a sacred landscape.

One of the most significant achievements of this era, alongside the eventual purchase of Hill Cumorah, was the reacquisition of properties connected with key figures such as Martin Harris and the Whitmer family. These sites carried deep symbolic importance. The Harris home was associated with one of the Three Witnesses of the Book of Mormon, and the Whitmer farm in Fayette was the place where the Church itself was formally organized in 1830. By the early twentieth century these locations had passed through many hands, and recovering them required not only money but trust. It was here that the Beans’ decades of relationship building bore fruit.

Willard’s steady presence in community affairs and Rebecca’s quiet charity gradually turned suspicion into respect. Their neighbors came to see that the Mormon family at the Smith farm was not seeking to exploit or dominate, but simply to live as Christians among them. This change in sentiment mattered greatly when Church leaders approached families about purchasing historic parcels. The same community that had once bristled at the very name of Mormonism began to allow negotiations to proceed with less hostility. The Beans’ example softened the ground so that others could sow.

“Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called the children of God.”

— Matthew 5:9

In practical terms, the Beans often served as the eyes and ears of the Brethren. When rumors circulated that certain parcels might be available, they relayed information promptly. When local resistance threatened to derail conversations, they provided counsel on how best to approach families. At times they themselves became the face of negotiations, representing the Church with humility and sincerity. Though their names do not always appear in formal records of purchases, their fingerprints are evident throughout the process.

By the late 1920s and 1930s, the Church had secured a number of historic properties across New York that together formed a tapestry of sacred memory. The Smith farm, the Sacred Grove, Hill Cumorah, the Whitmer farm, and associated landmarks were gradually woven back into the care of the Saints. This would not have been possible without the labor of Willard and Rebecca, who transformed hostility into openness and suspicion into welcome.

For Latter day Saints today, it is easy to take for granted that these places are preserved, marked, and maintained by the Church. Yet each acquisition was the fruit of years of patience, sacrifice, and faith. The Beans remind us that Zion is not built overnight. It is built by families who consecrate their lives to the Lord’s work, often in obscurity and with little recognition at the time.

“Wherefore, be faithful; stand in the office which I have appointed unto you; succor the weak, lift up the hands which hang down, and strengthen the feeble knees.”

— Doctrine and Covenants 81:5

Family, Faith, and Community

The mission of Willard and Rebecca Bean was not one of solitude. Though called as a missionary couple, they were a family from the very beginning. Just months after arriving at the Joseph Smith farm, Rebecca gave birth to a daughter in the very home where Joseph himself had once lived. They named her Palmyra, a name chosen both to honor the town where she entered the world and to bind her life to the sacred heritage of that place. In time three sons would join her, each of them growing up on the same soil where angels had ministered and prophets had prayed.

Willard, Palmyra, Alvin Pliny, Rebecca (seated), Dawn, and Phyllis (daughter of Willard and Gussie).

Family life in the Smith farmhouse was a blend of the ordinary and the extraordinary. The children did chores like any others, fetching water, tending gardens, and helping their parents with household work. Yet their surroundings were unlike any other childhood home. Their playrooms were the very rooms where Joseph Smith had studied the scriptures. Their backyard was the lane that led to the grove of trees where the heavens had opened. Their bedtime stories were not only tales from the scriptures but also personal testimonies of the events that had occurred on the very ground beneath their feet. For the Bean children, history was not distant. It was the air they breathed.

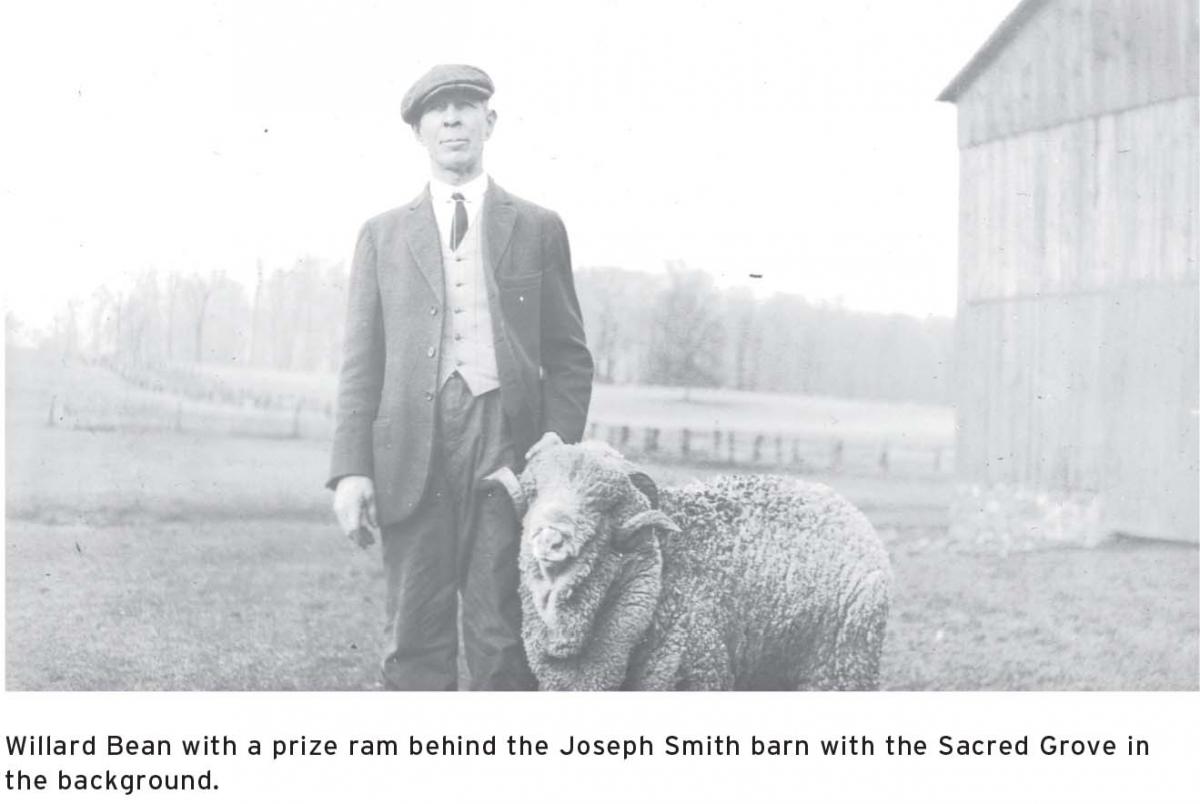

Rebecca made the home a place of warmth and holiness. Her homemaking was not separate from her missionary service; it was her missionary service. Each meal served to guests, each hymn sung at the piano, each comforting word to a tired visitor was an act of consecration. She taught her children to see the home itself as a sacred trust, one they were privileged to guard. Willard, while managing the farm and guiding tours, also taught his children lessons of strength, faith, and perseverance. He had once been known as the “Fighting Parson” for his boxing skills, but here his fight was not in the ring. It was in showing his sons and daughters that a man’s true strength lies in his testimony and in his love for others.

“Train up a child in the way he should go, and when he is old, he will not depart from it.”

— Proverbs 22:6

The Beans also became part of the broader community in small but meaningful ways. At first they were outsiders, yet as years passed, they were drawn into civic life. Willard joined local organizations and offered his talents to community projects. Rebecca became known as a neighbor who could be relied upon in times of need. Their children attended local schools, where at first they endured prejudice but gradually won friends by their kindness and diligence. Over time the Bean family was no longer seen as “the Mormons who lived at the Smith farm” but as fellow citizens who contributed to the well being of the town.

The rhythm of their days reflected both family devotion and missionary labor. Mornings might begin with milking cows or harvesting from the garden, followed by welcoming a group of visitors who had traveled across the country to see the Smith farm. Afternoons were filled with chores, school lessons, or tending to community needs. Evenings often brought cottage meetings where hymns were sung and testimonies borne. In all of it, the Beans showed that missionary work was not only preaching the gospel but living it in every detail of life.

Their example demonstrates a truth still relevant today. A family that places Christ at the center becomes a beacon to all around them. The Beans did not persuade Palmyra with lofty sermons. They persuaded by showing what a covenant family looks like. They revealed the gospel by the way they worked, the way they loved, and the way they endured hardship with faith.

“Ye are the light of the world. A city that is set on a hill cannot be hid.”

— Matthew 5:14

Release and Farewell

After nearly a quarter of a century, the long mission of Willard and Rebecca Bean drew to its close. In 1939, the First Presidency released them from their assignment at the Joseph Smith farm. What had begun as a five year call had stretched into twenty four years of service, sacrifice, and quiet triumph. By then their children were grown, the farm was firmly in the hands of the Church, and Palmyra itself had been transformed. What once had been a place of suspicion had become a place of reverence and welcome.

The farewell was not without emotion. When the Beans had first arrived in Palmyra, many neighbors would not greet them on the street. Now those same neighbors expressed sorrow to see them go. Civic leaders who once kept their distance now honored them as valued citizens. Merchants who once closed their doors now extended gratitude. The people of Palmyra, once wary of the Mormon presence, had come to admire the family who lived in the Smith homestead with such dignity and devotion.

The Beans themselves looked back on their mission with humility. They did not see themselves as heroes but as ordinary Saints who had done their best to serve the Lord. They had planted gardens, baked bread, guided visitors, and spoken kindly when others were cruel. They had raised children in a town that did not always welcome them, and they had turned that very town into a place of friendship. Their legacy was not only in land recovered or buildings preserved. It was in hearts softened and in a community changed forever.

“Well done, thou good and faithful servant: thou hast been faithful over a few things, I will make thee ruler over many things: enter thou into the joy of thy lord.”

— Matthew 25:21

Returning to Utah was both joyful and difficult. They reunited with family, breathed the air of the mountains they had left behind, and settled again into the community of the Saints. Yet their hearts would always remain partly in Palmyra. The Smith farm had been their home for nearly a generation. Their children had taken their first steps there, had learned their first lessons of faith under its roof, and had played among the trees of the Sacred Grove. The farm was more than an assignment; it had been their consecrated life.

The Church, meanwhile, continued the work the Beans had begun. New caretakers were called, professional conservation practices were introduced, and the sites were gradually developed into the historic landmarks we know today. Conferences, pageants, and commemorations would all take place on the soil the Beans had protected. Every visitor who walked through the homestead or entered the grove did so because one family had kept the place alive when it might otherwise have been forgotten.

For Palmyra itself, the departure of the Beans left a mark of gratitude. They had proven that Latter day Saints could be trusted neighbors and friends. They had bridged a gap of nearly a century between the expulsion of the early Saints and the respectful presence of the modern Church. The farewell of the Beans was not the closing of a chapter but the opening of a new one, in which Palmyra and the Church could look at one another not with enmity but with mutual respect.

“And they shall be mine, saith the Lord of hosts, in that day when I make up my jewels; and I will spare them, as a man spareth his own son that serveth him.”

— Malachi 3:17

Legacy and Lessons for Today

The story of Willard and Rebecca Bean is not simply a chapter in Church history. It is a living example of how God accomplishes His work through faithful families. Their mission reminds us that sacred places are preserved not only by money and deeds but by consecrated lives. For nearly a quarter of a century, the Beans gave their time, their strength, and their family to the service of the Lord. In doing so, they not only secured the Smith farm and the Sacred Grove but also prepared the way for the acquisition of Hill Cumorah and other historic sites. More importantly, they healed a community that had once turned its back on the Saints.

One lesson from their story is the value of patience. The Beans did not change Palmyra overnight. For years they endured rejection, prejudice, and cold shoulders. Yet they continued in quiet service, believing that kindness would eventually melt hostility. Their experience shows that missionary work is often measured not in days but in decades, not in dramatic conversions but in steady acts of charity. Modern missionaries, families, and wards can learn from this example. True conversion—whether of an individual or of a community—requires endurance and love unfeigned.

“Let us not be weary in well doing: for in due season we shall reap, if we faint not.”

— Galatians 6:9

Another lesson is the sanctity of place. The Beans understood that holy ground must be treated with reverence. They tended the Smith farm not as caretakers of property but as stewards of memory. They guided visitors into the Sacred Grove with a sense of awe, encouraging them to pray and receive revelation for themselves. Their reverence teaches us that temples are not the only holy places. Our homes, our chapels, and even the quiet groves of our own lives can become sacred if we invite the Spirit to dwell there.

The Beans also remind us of the power of family consecration. Their children were not bystanders but participants in the mission. They grew up in a home where missionary service was the daily rhythm of life. They learned that faith is not something reserved for Sunday meetings but something lived in the kitchen, the classroom, and the field. Modern families can draw strength from this example. When parents and children alike dedicate themselves to service, the home itself becomes a missionary tool.

“And they did teach their children that they should look forward with steadfastness unto Christ.”

— Jacob 4:5

Their story further testifies that the Lord often calls the unlikely to accomplish the impossible. Willard Bean was a boxer, not a scholar or a preacher. Rebecca was a homemaker, not a public figure. Yet God called them to represent the Church in a town filled with suspicion, and He magnified their efforts until they became instruments in His hands. The Restoration has always followed this pattern. From a boy prophet in a grove to a missionary couple on a farm, God chooses ordinary people and turns their lives into extraordinary testimonies.

For the Church as a whole, the Beans’ mission underscores the importance of preserving history. Without their decades of stewardship, many sacred places might have been altered beyond recognition or lost entirely. Because of their sacrifice, millions of Saints today can visit Palmyra, walk the Smith farm, and kneel in the Sacred Grove. Every testimony borne in those places is, in part, the fruit of their labor. Their legacy belongs not only to their descendants but to every member of the Church who has ever felt the Spirit whisper in those woods.

“Remember how great things he hath done for you.”

— 1 Samuel 12:24

In the end, the Beans’ story is not about fame or recognition. It is about faith. They did not seek to be remembered, yet their example continues to inspire. They remind us that consecration is not only about what we give to the Church but about how we live each day in our homes and communities. They remind us that the Restoration is not locked in the past but is a living story that requires living witnesses. And they remind us that even in the most difficult callings, God sustains His servants when they choose to endure in faith.

Their mission closed in 1939, but their legacy is still unfolding. Every child who kneels in the Sacred Grove, every family who walks the Smith farm, and every missionary who bears testimony of Joseph Smith’s First Vision stands on the foundation that Willard and Rebecca Bean built. Their story is not finished, because their influence continues wherever faith is renewed and wherever the Restoration is remembered.

Conclusion: The Beans’ Legacy and the Ongoing Call

Lessons for Families

For families, the Beans’ example is particularly powerful. They raised their children in an atmosphere of sacrifice and consecration. They showed that family unity is strengthened not by comfort but by shared purpose. Their children were not deprived by growing up in a place where they were often outsiders. Instead, they were enriched by the example of parents who lived their covenants fully.

Modern parents can learn from this. In an age where distractions are many and faith is often dismissed, the Beans teach that a family rooted in Christ can withstand social pressures. They remind us that the home itself is a mission field, and that children thrive when they see parents living with conviction.

Lessons for Missionaries

For missionaries, the Beans’ mission is a reminder that success cannot be measured only in baptisms. The Beans baptized very few people in Palmyra. Yet their mission was one of the most successful in Church history. Why? Because it laid a foundation for future generations. It changed hearts slowly, quietly, and permanently.

Missionaries today, whether serving across the globe or in their own communities, can take courage from the Beans. Sometimes the work feels invisible. Sometimes it seems that progress is slow. But God sees the long view. A seed planted today may not bear fruit until decades later. The Beans lived long enough to see some of their fruits, but much of their harvest came after they had gone. Their patience is a sermon for every young man and woman who feels discouraged on their mission.

Lessons for the Church

For the Church as a whole, the Beans’ story reinforces the importance of sacred spaces. The acquisition of the Smith farm, the Hill Cumorah, and the Sacred Grove was not about real estate. It was about preserving testimony. These places serve as physical witnesses of spiritual truths. Standing in them reminds us that the Restoration was not abstract, it was real. It happened in a grove of trees, on a quiet farm, in a small town that once rejected and later embraced the Saints.

The Church continues to emphasize this today. Official pages on the Joseph Smith Birthplace and Palmyra historic sites invite families and missionaries to see the very places where God’s work began anew. These pages echo what the Beans first taught visitors: that the Restoration is not only read about, it is experienced.

A Call for Modern Saints

Perhaps the greatest lesson of the Beans’ mission is that every member of the Church is called to be a caretaker of sacred things. Not all are asked to live on a historic farm, but all are asked to preserve faith in their homes, to defend truth in their communities, and to make their families places where the Spirit dwells.

In that sense, the Beans’ call continues today. Each Latter-day Saint is asked to be a steward, not only of land or buildings, but of testimony. Like Willard and Rebecca, we may be placed in environments where we are misunderstood or unwelcome. Like them, we may face suspicion or hostility. And like them, we are asked to endure, to serve, and to show Christlike love until hearts are changed.

“Therefore, dearly beloved brethren, let us cheerfully do all things that lie in our power; and then may we stand still, with the utmost assurance, to see the salvation of God.”

— Doctrine and Covenants 123:17

A Legacy That Lives On

In the end, the Beans’ mission was not about a house, or even a farm. It was about healing a wound between a town and a faith. It was about proving that faith, patience, and charity can transform even the hardest soil. Their twenty-four years in Palmyra were a living parable of Christ’s command to love one another.

Today, as thousands of Saints kneel in the Sacred Grove or climb the Hill Cumorah, they are walking in the shadow of the Beans’ service. Every whispered prayer, every tear shed in gratitude, every testimony strengthened in those holy places is part of their harvest. Their mission lives on because they consecrated their lives to God’s work.

The Beans’ story is not merely history. It is prophecy fulfilled. It is evidence that God can take an ordinary family and make them instruments of healing and preservation. It is a call to every Latter-day Saint to rise to the work, to defend the Restoration, and to consecrate our lives, as the Beans did, to the kingdom of God.

Several images courtesy https://rsc.byu.edu/

3 comments

Pingback: A Family’s Faith That Healed a Town | FFFJ Alliance

Pingback: Ordinary Family, Extraordinary Courage | Heroic Outfitters

Pingback: The Palmyra Beans: A Look at LDS History and Sacred Locations - Trek.pub